This is NOT just a rural EMS issue – EMS systems across the country are in the midst of a financial and staffing crisis, urban and rural.

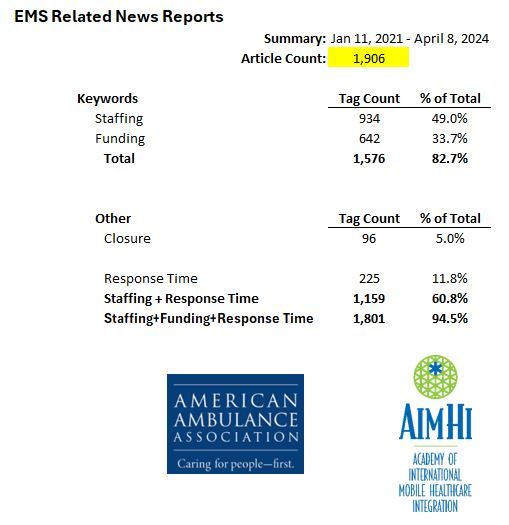

In a rolling tally of local and national media reports since January 2021, of 1,053 local and national media report about EMS, 347 reports are about the funding crisis, and 623 are about the staffing crisis. EMS leaders know the 2 issues are linked. This means 92% of media reports are about funding and staffing challenges for EMS systems.

---------------------------------

What if the ambulance doesn't come? Rural America faces a broken emergency medical system

Nada Hassanein

USA TODAY

June 26, 2023

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2023/06/26/no-ambulances-closing-hospitals-the-crisis-facing-rural-america/70342027007/

Melissa Peddie, EMS director and paramedic, drives the single ambulance that serves Liberty County in rural north Florida.

During any shift, there are just two full-time paramedics driving the lone truck around the 1,176-square-mile sparsely populated county.

Just a couple of weeks ago, Peddie and her husband, the local fire chief, drove their own car to stabilize an older man who fell and was unable to get up – the ambulance was on another call. The couple waited with the patient and his family until an ambulance from a county 30 minutes away could come to take him an hour east to Tallahassee, the state capital and home to the nearest trauma center hospital.

“We've done that quite often,” she said. “Jump in my car and go to the scene and stabilize, maintain until a crew or somebody can get there.”

Often, she must call two or three neighboring counties to find an ambulance for mutual aid.

Nearly 4.5 million people across the U.S. live in an "ambulance desert" – 25 minutes or more from an ambulance station – and more than half of those are residents of rural counties, according to a new national study by the Maine Rural Health Research Center and the Rural Health Research Centers.

As rural hospitals shutter across the nation, dwindling emergency medical services also must travel far to the nearest hospital or trauma center. Experts and those in the field say EMS needs a more systematic funding model to support rural and poorer urban communities.

“This is a really extreme problem, and we need to figure out solutions. People think that when you call 911, that someone's coming in,” said lead author Yvonne Jonk, deputy director of the Maine Rural Health Research Center. “Most people don't realize that their communities don't actually have adequate coverage.”

'In crisis mode'

About 15% of the U.S. population lives in rural areas like Peddie’s Liberty County, where poverty and mortality rates are higher than in urban areas.

Four of 5 counties across the nation have at least one ambulance desert, according to Jonk’s analysis of 41 states and data from 2021 and 2022.

Some regions are more underserved than others: States in the South and the West have the most rural residents living in ambulance deserts.

Eight states − Nevada, Wyoming, Montana, Utah, New Mexico, Idaho, South Dakota and North Dakota − have fewer than three ambulances covering every 1,000 square miles of land area.

In North Dakota, more than 31,000 people, about 4% of the total state population, live in ambulance deserts, according to the analysis.

PJ Ringdahl, regional adviser for the North Dakota EMS Association and paramedic, advocates for EMS stations across the state and holds listening sessions with other paramedic and emergency medical technicians.

“We're all in crisis mode. We're all short-staffed. And we really have to try to figure out an appropriate model to be able to deliver health care to those communities,” Ringdahl said.

Throughout the West, many of those communities are underserved American Indian reservations.

In 2015, a Colorado-based emergency medicine physician and his wife used their retirement money to fund two ambulance stations in a North Dakota ambulance desert, the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, where trucks would have to rush to emergencies from at least a half-hour away.

Meanwhile, the Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone Tribe awaits help. The reservation stretches along the Nevada-Oregon border near Idaho and has no ambulance or hospital. Nevada has just 55 ambulance stations across the state, according to the analysis, and about 33% of the ambulance desert population is in rural areas.

Tribal chairwoman Maxine Redstar said the community used to have an ambulance service, but it couldn’t afford to keep it going.

“When you call an ambulance, it comes from Winnemucca," she said, "which is an hour away."

Weather, wildlife and long, dark winding gravel roads make getting to the scene difficult.

That's the case on the Duckwater Shoshone Tribe Reservation in the central Nevada desert valley, which doesn't have an ambulance, and the nearest one is an hour away. Tribal members take matters into their own hands. Janey Blackeye Bryan, 60, started first aid training as a teenager and became certified in community emergency response, then volunteered as an advanced EMT for years. Her daughter and son-in-law are volunteer EMTs, and her husband is a volunteer firefighter.

"We've got medical issues here. You got to move somebody, you got to get them someplace really quick," Bryan said. But

"we're located about 75 miles away from an emergency room. ... There is no golden hour."

Inconsistent funding models jeopardize lifesaving services

Few states designate EMS as essential services. In the U.S., EMS are mainly funded by local governments, and not all states allocate supplemental funds toward the services. In communities like Peddie’s, for example, the county’s general revenue budget must pay the bill, because supplemental state funding falls short. In addition, an EMS agency typically doesn’t receive reimbursements by insurance companies unless a patient is taken to an emergency room.

“There's no systematic way to go about funding,” Jonk said. “It varies state to state as to how much funding they have at their disposal to throw at ambulance services.”

Amid patchwork funding, communities rely on varied revenue sources to fund ambulance services, said Lindsey Narloch, project manager at Rural EMS Counts, a North Dakota EMS improvement project. That often doesn’t cover expensive equipment, medication and staff salaries. Counties end up having to pay most of the cost.

“It's kind of a hodgepodge of a little reimbursements, some tax funds, some grants, volunteer labor,” she said.

Poorer communities end up taking the brunt. High-income areas with larger proportions of white patients had shorter response times compared to poorer areas, according to one study of cardiac arrest emergencies and ambulance response.

Unpaid volunteers often fill gaps. But that workforce is under threat as volunteers age and recruitment for new volunteers becomes more difficult.

Recently, Gary Wingrove, president of The Paramedic Foundation, a Minnesota-based nonprofit, gave a presentation to policymakers and shared the story of a Wyoming-based volunteer EMT who drives to a community 300 miles away to fill in as a paramedic for one week a month.

“One major problem we have is the payment system does not support full-time ambulance personnel,” Wingrove told USA TODAY. Funding needs to be sustainable and prevent volunteers from "having to drive 300 miles to do a full-time job and instead get paid" to serve their local communities.

Critical access hospitals, which are medical centers in rural, underserved communities often with a high number of uninsured residents, are paid more than other hospitals if their care delivery cost is higher than the standard Medicare payment, he said.

Amid rural hospital closures and reliance on volunteerism, “we need something similar for rural ambulance services,” he said. “We have to take a hard look at our financing of rural ambulance services. And to me, it just makes a lot of sense if we create a system like the critical access hospitals have for the rural ambulance services."

‘Forgotten about’

EMS professionals are first responders but also health care providers, Ringdahl said, adding she wishes to see the service more supported within the U.S. health care delivery system.

“The EMS profession needs a home,” she said. “EMS kind of sits on two sides. … So, when you don't have a home, sometimes you just get left behind. On a federal level, I'd like to see some initiative to maybe get us a little bit more rooted into that health care system.”

On top of delivering critical health services, in rural areas EMS workers often must navigate rough terrain.

“For a long time, we've done this on the backs of volunteers,” Narloch said. “There has to be a recognition that this is something that has to be paid for, and you have to pay people well to do. It's a big job.”

Working a call recently, Peddie was in an accident that totaled her ambulance. The county now uses an older backup truck that Peddie fears will break down. A new vehicle would set the county back up to $300,000, she estimated. Manufacturers estimate a single vehicle can cost anywhere from $120,000 to $325,000.

“We’re already in a major deficit,” she said. “You hope that your equipment stays intact and works.”

Peddie said her profession is overlooked as a critical service.

“We're forgotten about,” she said. “The moment someone needs us, they think about us. But after that, it's just a fading thought.”

Reach Nada Hassanein at nhassanein@usatoday.com or on Twitter @nhassanein.